The electricity comes from the socket. But how does the electricity get into the socket? On the road with the guys who make the houses shine.

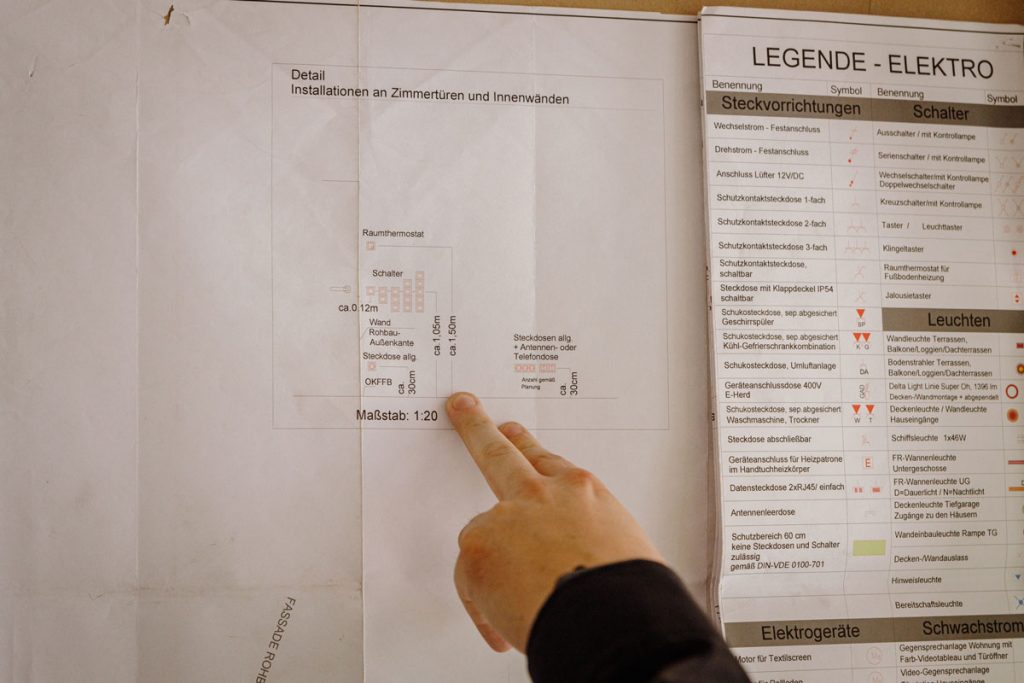

They lay tens of thousands of cables, they install thousands of sockets, flat by flat they work their way forward. René Haack, 38 years old, and his boys from Elektro-Kohl Berlin. Their work happens in secret. All the cables, which now lie neatly next to each other like the lanes of a motorway and meander through the rooms, will later disappear behind the wall or under the floor. So it is all the more important now that they work 100 per cent correctly. “We electricians have a zero percent fault tolerance,” says Haack. If the light switches are to be mounted at a height of 105 centimetres, the cables must also reach 105 centimetres.

René Haack has a cheerful, friendly manner. Not one to grouch at his boys, but gives objective and clear instructions. When you talk to him, you notice that what he is doing gives him pleasure. “Our work has to be planned with the general staff,” he says. There are the drywall builders, who put up the walls in the houses. The electricians are always one step behind. There are the plumbers, who are responsible for the water and drains, with whom they work side by side. Haack has to come to an agreement with all of them, so that they are not in each other’s way, so that everyone knows what they have to do and when.

His father was at Siemens, so René Haack also went to Siemens when he was young. “Siemens was a tradition here,” he says. His apprenticeship was called: IT systems electronics technician. “In my time there were still cat’s heads when you did something wrong,” he says. Cat heads? Haack suggests a blow to the back of the head. But Haack wanted more, was still training as a specialist for purchasing and logistics, and increasingly took over the planning work for construction sites. Now he is still doing his master craftsman’s job, he goes to school once more, right after work.

In the morning at 5.30 a.m. he starts off, picking up the boys and the necessary tools at the farm, then driving to the construction site, going through the daily routine, distributing the tasks, placing orders for materials, checking the work. Especially the latter is very important. Each cable has a function, one is for the washing machine, the other for the cooker, the next for the electric curtains. A shaft leads from the very bottom of the ground floor to the very top of the last floor. In it are the power cables that lead to the flats.

Afterwards you should not see any of this anymore. So the cables for the ceiling lighting in the lower flat run along the floor of the upper flat and only come back through a hole in the ceiling. These cables are still exposed, but soon they will be covered by a layer of concrete and no longer visible. “This is much more elegant than laying the cables under the plaster,” says Haack. The cables are laid between the drywall walls in a similarly elegant way and are thus hidden.

Haack was born in Wedding, Berlin and now lives in Spandau. When he drives through the city with friends or family, there is hardly a neighbourhood where he can’t point left and right and say: “I’ve already built there and there and there. He is proud of that. Proud of his invisible work, which the new flat owner only notices when the light comes on. And the washing machine. And the cooker …