When you move into your new domicile, you will gradually conquer the Spree peninsula yourself … stroll, stroll, stick your nose into a backyard. What is there to buy nearby? Where is the best food served? Can you perhaps find a favorite bank on the Spree?

We approach your future home with the question: Where is a bit of the past hidden in the surroundings?

There are no archaeological finds on the entire Spreehalbinsel. So we don’t have to go back that far. Fortunately. For many centuries our property was used as pasture for goats and sheep. The first detailed maps from the 1930s show a different road layout, a loose building development and some residential buildings along the Helmholtzstraße. The “Kolonie Pascalstraße” is first mentioned by name on a map from 1951.

Let us start our walk where the Landwehrkanal and the Spree meet. At this place we find a salt magazine on old plans. Salt is very fashionable today. But back then it was not about exclusive varieties like pink shimmering Himalayan salt. The salt for the salt magazine came from Halle an der Saale, among other places, and was extracted from brine there. Or from Staßfurt, where at the beginning of the 19th century the discovery of a million-year-old sea made salt affordable in the German-speaking world. It was urgently needed to preserve food. Today we can no longer imagine our lives without salt in our soup. And of course, in those days, seasoning food with the white grains was a welcome change in any cooking pot. The entire section of the Landwehrkanal bank from the Spreekreuz to the Tiergarten is still named after the former salt depot.

Houseboats on the Berlin Landwehrkanal (© Sir James)We leave the shore and walk northeast along Dovestraße. At the level of the bend to Helmholtzstraße, the Spree river on the left-hand side has a small indentation. There used to be an exemplary waste loading station. For 20 years, until the fifties of the last century, garbage trucks drove into a hall, emptied their garbage into a barge in the Spree and left the plant without getting in the way of the following garbage trucks. A smooth process – well thought out and effective. Aesthetically the building is besides and in such a way it was explained later as example of the architectural direction new building’ to the architectural monument.

If we now turn into Helmholtzstraße, there used to be a large bus depot on the left behind the waste loading station. If you open an issue of the “Deutsche Bauzeitung” of 1927, you will find a detailed description of the “spacious modern large garage”, as the author, a retired government architect, enthuses about the newly built hall. One learns interesting details such as: “The heating of the hall is designed as a low-pressure steam-circulating air heating system.”

The cleaning of the two-story vehicles is extremely intensive: “On entry, the vehicles are handed over to a yard coffer and are sent for dry cleaning. They then go through the warm wet cleaning process, followed by cleaning with cold water.” To take such a thorough bath after hard daily work – this is what some contemporaries in the area wanted. The hall is still standing – but buses are no longer washed there today.

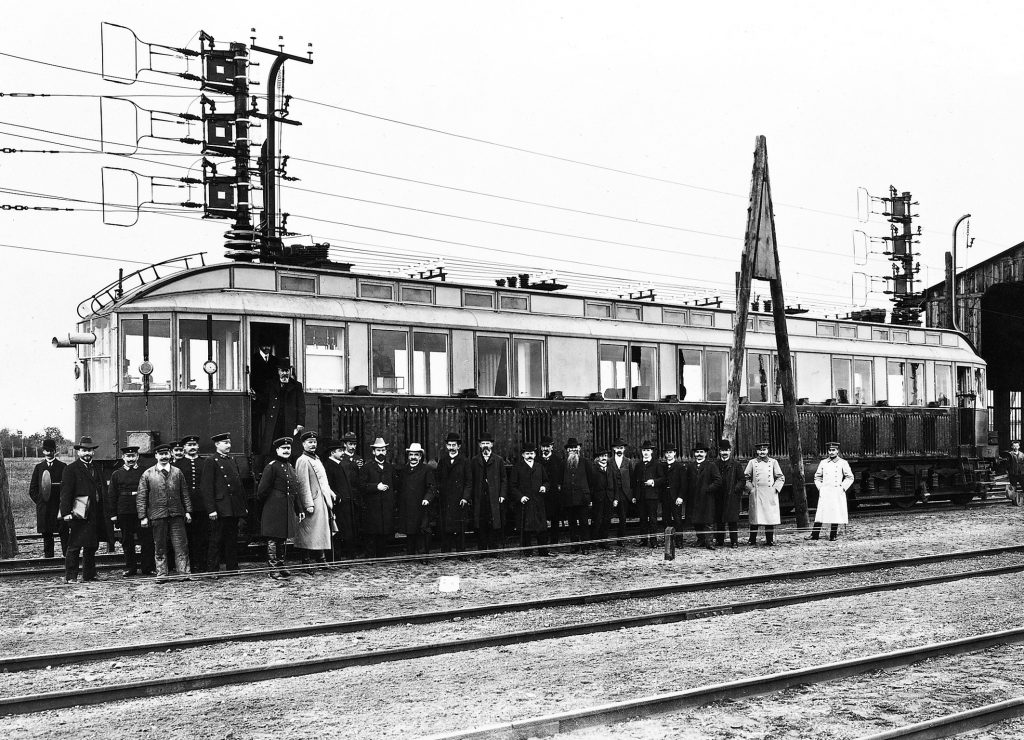

We continue along Helmholtzstraße in a north-easterly direction. Here you can see the former “Werk S” of Osram. The “S” stood for Siemens at the beginning of the 20th century. Within 50 years, Siemens had developed from a small workshop into a globally active electrical company, and with groundbreaking major projects such as telegraph lines and inventions such as the dynamoelectric principle, it had changed people’s lives radically. And also with light bulbs. For a while, Siemens had its main location down on the Salzufer (where we just came from), but then moved on to the west of the city.

Together with AEG and the inventor of the incandescent stocking, Carl Auer von Welsbach, Siemens founded the Osram company, which operated a light bulb factory here in Helmholtzstrasse. At a time when fierce competition and constant new developments were causing the production of incandescent lamps to expand at an exhilarating pace, this factory was also involved in enlightening more and more private households in Berlin. You won’t even consider the hidden installations when you press the switch next to the entrance door in your apartment in the Charlottenbogen and it is immediately brightly lit. For the people in former times this was an unbelievable, wonderful luxury for a long time.

Since we are now standing at the corner of Pascalstraße, we can almost see the Charlottenbogen from there. We walk in the direction of your new domicile and quickly dive back into our reality. If someone should be at home before you, it is already brightly lit.